Open Data and Fitness for Use: A Realistic Look

A basic assumption of the open data movement is that more intensive and creative uses of information and technology can improve policy-making and generate new forms of public and economic value.

Open data initiatives focus on:

- education

- public health

- transportation

- environmental stewardship

- economic development

Ironically, this information is often treated as a black box in the open data movement.

Stakeholders, analytical techniques, and technology tools all receive considerable attention, but the information itself is often seen as a given, used uncritically and trusted without examination.

However, data now being released as “open data” was actually collected or created for other purposes. It has undeniable potential value, but it also contains substantial risks for validity, relevance, and trust.

Government Data for Policy Analysis and Evaluation

Administrative data is attracting attention for its value inside and outside government.

This data reflects the operations of government programs through the operation of automated activities and electronic government services. Much of this data is collected in real time as these systems do regular processing. Transactional data reveals the workflow activities of case management systems or steps and results of customer service exchanges. Government-deployed sensor networks gather data about transport and air quality for regulatory purposes. Financial management systems record budgets, grants, contracts, cash flow, and reconciliations.

The open government movement is making these data sets readily available to the public through programs like Data.gov. It provides electronic access to raw, machine-readable information about government finances, program performance, trends, transactions, and decisions.

The goal is to allow people and organizations outside government to find, download, analyze, compare, integrate, and combine these datasets with other information to provide public value. This phenomenon is not limited to the federal level. States and municipalities are experiencing similar growth in data holdings and taking advantage of new technologies to gather and analyze data.

Some government data has been used by external analysts for decades.

Some government agencies have the responsibility and skill to collect, manage, maintain, and disseminate data and represent a long-standing commitment to provide social, economic, and demographic information. The census, economic, and other formal statistics produce well-understood and readily usable information because they apply the standards of social science research in data collection and management. They collect well-defined data on specific topics using well-documented methodologies that follow a logical design. The data files are managed, maintained, and preserved according to explicit plans that include formal rules for access, security, and confidentiality.

eGovPoliNet

The eGovPoliNet/Crossover Consortium, sponsored by the European Commission FP7 research program, is an expanding international network of research institutions investigating globally important data and technology challenges in policymaking.

As an NSF-funded consortium member, CTG UAlbany investigates how social networks, information, and technology influence policy analysis, decision making, and policy evaluation in different parts of the world.

Involvement in this international community enhances our work in the U.S. on the value and use of government data for governance, policy-making, and social and economic benefit.

Source of Information Problems

Information problems stem from a variety of causes that government information providers and independent analysts need to understand.

Conventional wisdom

A set of common beliefs and unstated assumptions are often substituted for critical consideration of information.

These include assumptions that:

- information is available and sufficient

- objectively neutral, understandable

- relevant to the task of evaluation

Left unchallenged, these assumptions compromise all forms of program assessment and policy analysis.

Emerging open data initiatives present similar problematic beliefs. They convey an unstated assumption that large, structured raw data sets are intrinsically better than processed data, and that data in electronic data is superior to other forms and formats for information. Thus machine-readable raw datasets receive more attention than better defined and potentially more suitable traditional datasets since there would be some data processing and the sets are not online.

Provenance

Much open data emerges from activities and contexts that are far different in purpose, context, and time from its eventual use.

Taken out of context, the data loses meaning, relevance, and usability.

Although the public may be offered thousands of data sets from one convenient Website, these resources are actually distributed among different government organizations, locations, and custodians. The datasets are defined and collected in different ways by different programs and organizations. They come from a variety of different systems and processes and represent different time frames and geographic units or other essential characteristics.

Most datasets come from existing information systems that were designed for specific operational purposes. Few were created with public use in mind. Metadata is essential to understand but unfortunately, metadata receives little attention in most organizations.

An administrative or operational dataset is usually defined at the point of creation in just enough detail to support the people who operate the system or use the data directly. As the underlying dataset or system changes over time, corresponding maintenance of metadata tends to be a low priority.

Practices

Research shows that in order to understand data, one needs to understand the processes that produce the data (Dawes, et al., 2004).

Data collection, management, access, and dissemination practices all have strong effects on the extent to which datasets are valid, sufficient, or appropriate for policy analysis or any other use (Dawes and Pardo, 2006).

Data collection schemes may generate weekly, monthly, annual, or sporadic updates. Data definitions and content could change from one data collection cycle to the next. Some data sets may go through a routine quality assurance (QA) process, others do not. Some quality assurance processes are rigorous, others are superficial. Some data sets are created from scratch, others are byproducts of administrative processes; still others may be composites of multiple data sources, each with their own data management practices.

Data sets may be readily accessible to internal and external users, or require some application or authorization process. They may be actively disseminated without cost or made available only by request or fee. Access may be limited to certain subsets of data or limited time periods. In addition, data formats are most likely the ones that are suitable and feasible for the organization that creates and manages the data and may not be flexible enough to suit other users with different capabilities and other interests.

Fitness for Use*

- Intrinsic quality most closely matches traditional notions of information quality including ideas such as accuracy and objectivity, but also believability and the reputation of the data source.

- Contextual quality refers to the context of the task for which the data will be used and considers timeliness, relevance, completeness, sufficiency, and value-added to the user. Often there are trade-offs among these characteristics (between timeliness and completeness, for example).

- Representational quality relates to meaning and format and requires that data not only be concise and consistent in format but also interpretable and easy to understand.

- Accessibility comprises ease and means of access as well as access security.

*Wang & Strong (1996)

Data Quality and Fitness for Use

Given the practical realities, even if government information resources are well-defined and managed, substantial problems for use cannot be avoided.

The term "data quality" is generally used to mean accuracy, but research studies identify multiple aspects of information quality that go beyond accuracy. Wang and Strong (1996) adopt the concept of “fitness for use,” considering both subjective perceptions and objective assessments, all of which effect how users willing and able to use information.

The current emphasis on open data plus the evolving capability of technological tools for analysis offer many opportunities to apply big data to complex public problems.

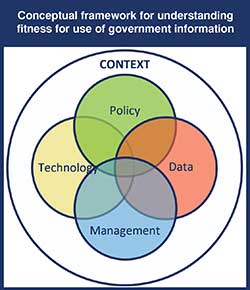

However, significant challenges remain before most government data can be made suitable for this kind of application. Policies, governance mechanisms, data management protocols, data and technology standards, and skills inside and outside government are needed if these information-based initiatives contribute to better understanding of critical social and economic issues and better policies to address them.

Conclusion

Open data presents both promise and problems.

We are more likely to achieve its promised benefits if we take a hard, realistic look at its character. One way to do this is to consider data in conjunction with the policies, management practices, and technology tools that create and shape it. Further, we need to understand how these considerations are embedded in social, organizational, and institutional contexts that influence data quality, availability, and usability.

Some challenges of government information use are technical problems addressing information storage, access, inquiry, and display. Management problems such as defining the rationale and internal processes of data collection, analysis, management, preservation, and access also exist. The challenges also represent:

- policy problems including examining the balance and priority of internal government needs versus the needs of secondary users

- resources allocated to serve both uses

- traditional information policy concerns with confidentiality, security, and authenticity

New sources of government data offer potential value for society – but the value will be realized only if government information policies and practices are better aligned with the needs of external users.

Likewise, analysts and other users need to take responsibility for assessing data sources and adjusting expectations and assumptions to more closely match the realities of data quality and fitness for use.

Sharon Dawes, Senior Fellow

Natalie Helbig, Senior Program Associate