Regional Coordination: Exploring new response capability

A crisis rarely occurs in one jurisdiction or community; they tend to cross multiple geographic and organizational boundaries. The effects of the World Trade Center attacks, for example, extended far beyond New York City and the effects of Hurricane Katrina were felt far beyond the city of New Orleans. Events such as these continue to generate new insights into the coordination across boundaries necessary to ensure effective response to incidents—both natural and man-made.

A crisis rarely occurs in one jurisdiction or community; they tend to cross multiple geographic and organizational boundaries. The effects of the World Trade Center attacks, for example, extended far beyond New York City and the effects of Hurricane Katrina were felt far beyond the city of New Orleans. Events such as these continue to generate new insights into the coordination across boundaries necessary to ensure effective response to incidents—both natural and man-made.

"The cost of not being prepared to share information, to coordinate our responses, and to work together is well understood. If we are unprepared, the next event will cause incalculable human misery . . ."

World Health Organization, November 2007

The 9/11 Commission highlighted the need for a new kind of cross-boundary coordination in emergency response efforts, stating that “the attacks on 9/11 demonstrated that even the most robust emergency response capabilities can be overwhelmed if an attack is large enough. Teamwork, collaboration, and cooperation at an incident site are critical to a successful response.” But as these events have taught us, coordination capability must be built long before a crisis. Investment in coordination prior to an incident is necessary to develop real understanding about roles and responsibilities, to build the institutional and individual relationships necessary to carry out those responsibilities, and to outline the requirements of an effective response. The range of possible incidents is unlimited, the resources to respond are not; building coordination capability is a necessary component of response preparedness.

What is “Infrastructure”?

The basic facilities, services, and installations needed for the functioning of a community or society, such as transportation and communications systems, water and power lines, and public institutions including schools, post offices, and prisons. American Heritage Dictionary

The nation’s critical infrastructure is receiving an increasing amount of attention in terms of creating new and more coordinated response capability. Key stakeholders are coming together in a variety of sub-domains of the critical infrastructure such as power, communications, transportation, and water to ensure continuity of operations. One strategy being implemented in some domains and explored in others is regional coordination. Regional coordination links together stakeholders in close proximity to one another to pursue joint or similar goals and responsibilities.

Regional coordination efforts are being organized to provide a forum for teamwork, collaboration, and cooperation to occur through physical and virtual co-location. The challenge to coordinating incident response efforts within regions is that coordinated response requires leveraging currently held resources in innovative and potentially more efficient ways, as well as establishing new business processes, communication flows, and a system of governance that satisfies the needs of all stakeholders. In addition, trust, collaboration, and timely cross-boundary information sharing all play a pivotal role in this new model.

"The time of a crisis is not the occasion to start sharing business cards!"

Participant, Protect New York Conference

Regional Coordination and the Telecommunications Infrastructure

The telecommunications infrastructure represents a unique set of challenges to coordination efforts because while privately owned, it is regulated by government. Government agencies and private sector organizations are jointly responsible for the communications infrastructure. Ultimately, continuity of operations, both governmental and private sector, is at the heart of any critical infrastructure incident response effort. Regional coordination strategies have the potential to improve these response efforts if they enhance the capability that exists without creating unnecessary duplication of effort. At the core of any strategy is securing coordinated access to real-time data to support informed decision making across four stakeholder groups: government, telecommunications providers, the private sector, and citizens.

Drawing on the reviews of the 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina responses, which cited the need for stronger national as well as regional preparedness, the organizations responsible for the telecommunications infrastructure are exploring ways to develop regional coordination capability. In particular, they are seeking ways to respond to the broad recommendation that coordination efforts must “be tailored to meet the needs of specific regions.” The recommendations, together with success in efforts at the national level and encouragement from the telecommunications community, have raised interest among states and localities as well as providers about the creation of regional coordination of telecommunications incident response as a complement to existing state and local level incident response capabilities. These coordination efforts have focused in four key areas: information needs, information sharing, relationship building, and the public value of coordinated response efforts.

Information: Key to a Coordinated Response

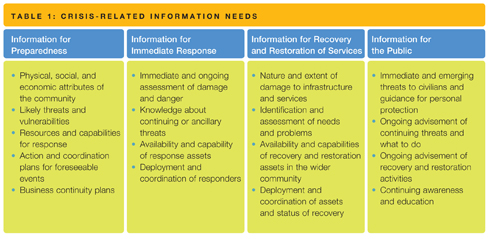

To respond to an incident, regardless of its severity, managers of the critical infrastructure need information about that incident—both their own and that of others— in order to react. Successful incident response cannot occur without reliable access to accurate information. CTG’s report, Information, Technology, and Coordination: Lessons from the World Trade Center Response, identified four critical categories of crisis-related information needs: for preparedness, immediate response, recovery and restoration of services, and for the public (see Table 1 below). These information needs span the duration of the crisis and extend from preparation to assessment.

Information was critical to the 9/11 recovery effort, where “it’s existence, availability, quality and distribution clearly affected, sometimes dramatically, the effectiveness and timeliness of the response and recovery efforts.” The most recent draft of the new National Response Framework, which the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) published in January of 2008, speaks to the critical role of information in crisis response.

Information was critical to the 9/11 recovery effort, where “it’s existence, availability, quality and distribution clearly affected, sometimes dramatically, the effectiveness and timeliness of the response and recovery efforts.” The most recent draft of the new National Response Framework, which the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) published in January of 2008, speaks to the critical role of information in crisis response.

For an effective response, expertise and experience must be leveraged to support decision-making and to summarize and prioritize information rapidly. Information must be gathered accurately at the scene and effectively communicated to those who need it. To be successful, clear lines of information flow and a common operating picture are essential.

To provide an effective response to an incident, disaster response teams need pertinent details about that incident. In the most basic terms, they need information. When a response team is built from multiple organizations or relying on information from multiple organizations, coordination across the boundaries of those organizations becomes key.

Information Sharing

Governments around the world are increasingly turning to information sharing as a lead strategy for developing response capacity for problems in a wide range of program and policy areas. Developing cross-boundary information sharing to support government response capacities requires change—in some cases, significant change—in policies, procedures, processes, and systems. These changes require new capability in technology certainly, but also in group decision making, learning, understanding, trust building, and conflict resolution, among others. Many organizations are just beginning to understand how difficult it is to create information sharing capability both in normal times and in times of crisis.

Cross-Boundary and Cross-Sector Relationships

Research and experience show that trust plays a significant role in the building of public-private partnerships where issues of confidentiality, proprietary information, and differing organizational cultures may arise and clash. Although both government and the private sector may have similar goals, they have different expectations about the type and amount of information that needs to be shared and how that information should be used once shared.

Within the telecommunications infrastructure, telecommunications incident reporting requires adept management of both organizational and technological resources. While private sector telecommunications providers are required to report information about threats to the critical infrastructure, government regulators still heavily rely on trust and cooperation as a means to gather sensitive data. Trust (or mistrust) develops out of the joint experience of working together. By observing how different individuals or organizations deal with risk and vulnerability, we learn to expect certain behaviors. Managing the cross-boundary sharing of information about telecommunications security requires sensitivity to both government and private sector needs, while remaining true to the public value of ensuring a secure communication network.

The Public Value of Regional Coordination

Altering a familiar and established crisis management response framework is a risky endeavor. The new response framework may duplicate the same problems in the current response or, worse yet, create new and unfamiliar problems. Ultimately, regional coordination should only be considered if it enhances the system that currently exists without institutionalizing redundancies. One way to assess the potential added value of new regional coordination capability is to use CTG’s Public Value Framework to consider the value in two ways:

- By improving the value of the government itself from the perspective of the citizens, and

- By delivering specific benefits directly to persons, groups, or the public at large.

To enhance the public value of investments in regional coordination these efforts should produce response capability that increases both the likelihood for continuity of operations of government in times of crisis and the quality of service in normal times.

General recommendations for regional coordination

In a recently completed CTG project focused on regional coordination for telecommunications incident reporting, key stakeholders from the telecommunications infrastructure in New York State brainstormed a list of recommendations for moving forward with regional coordination in that sector. Based on those specific recommendations and conclusions, CTG offers the following general recommendations for regional coordination:

- Jointly establish guiding principles. Bring together key actors from across the sectors to collaboratively establish guiding principles.

- Learn from others. Conduct current practices in regional coordination efforts. Research should specify focus on regional coordination of telecommunications incident response, in addition to models for governance and information sharing agreements of existing regional response efforts.

- Learn from yourself. Increase knowledge sharing about information resources, practices, and capabilities among key stakeholders and avoid duplicating response capabilities in either the public or private sectors.

- Act on new shared knowledge. Develop information flow models through collaborative group model building sessions to create shared understanding of where information is needed and how it gets to those places from where it is captured. Use new models of information flow and the results of recommendations 1, 2, and 3 to create necessary policies, procedures, and systems.

- Secure funding for continued exploration. Continue to assess progress and make assessments of impact as a strategy for securing funding for ongoing capability development efforts.

Donna Canestraro, Program Manager, Center for Technology in Government